One of our early offices was at: The Farm, (founded 1974) also known as Crossroads Community.[1]: 43 It was an environmental art and performance art project that also operated as a community center. The Farm was located at the corner of Army Street (later renamed Cesar Chavez Street) and Potrero Avenue in San Francisco, California, from 1974 to 1987.[2][3][4] It was founded by Bonnie Ora Sherk and Jack Wickert in 1974.[1]: 43 The open space incorporated a major freeway interchange and is now site of Potrero del Sol Park (formally La Raza Park).[5]

Sherk referred to the thirteen year-long project as an “environmental sculpture” where edible crops were grown, livestock were raised and educational programming took place. Sherk spoke of the project: “We’re attempting to reconnect people and humanize environments” and that the “growth process in life is like the creative process in art.”[2]

History

“In the city, things tend to be very fragmented, and the freeway is a symbol of that fragmentation,”

–Bonnie Ora Sherk[2]

Adults and children would gather at The Farm which was across a park from Buena Vista Elementary School. Children from Buena Vista would visit the Farm for field trips or go to the Farm after school.

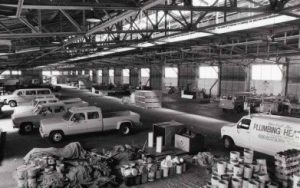

The Farm had a two-story building; the lower story contained an actual farm, with vegetable gardens, chickens, geese, rabbits, and goats.[3] Upstairs was a library and an art gallery. Also on the bottom level was a pre-school. The Farm would put on DIY shows to raise funds.

Sherk departed in 1980 after the city parks department decided to reclaim one of the Farm’s lots and turn it into a traditional urban park. Later directors turned the Farm into a punk rock showcase by night,[1]: 52–53 by partnering with mobile garage productions run by Craig Shell and Bill Gould (of faith no more), infamous for staging seminal 1980s punk rock bands such as Frightwig, Discharge, Camper Van Beethoven, the Descendents, the Mentors, 7 Seconds, MDC (Millions of Dead Cops), RKL (Rich Kids on LSD), Dirty Rotten Imbeciles, Raw Power, the Accused, Redd Kross, Soundgarden, the Gits, the Lookouts (early band of Green Day drummer), Bad Brains, and many more.

’80s punk shows at The Farm, such as the Black Flag / Redd Kross show on November 16, 1984, attracted notable figures including Kevin Thatcher and Mofo of Thrasher Magazine, along with members of The Faction.[6]

Buildings in the same complex also housed Survival Research Laboratories, Goforaloop Gallery, Subterranean Records, and CoreOS.

- Blankenship, Jana. “The Farm by the Freeway”. In Auther, Elissa, and Lerner, Adam, eds. (2012). West of Center: Art and the Counterculture Experiment in America, 1965–1977. University of Minnesota Press.

- Genzlinger, Neil (2021-11-19). “Bonnie Sherk, Landscape Artist Full of Surprises, Dies at 76”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-05-04.

- Carlsson, Chris. “The Farm”. FoundSF. Retrieved 2022-05-04.

- “In SF, art still thrives — and celebrates its history — at The Farm”. Mission Local. 2017-11-09. Retrieved 2022-05-04.

- Robertson, Michelle (2021-08-25). “The coolest new music venue in SF is a farm in the Bayview”. SFGATE. Retrieved 2022-05-04.

“Black Flag / Redd Kross: November 16, 1984”. Do You Remember ROCK ‘N’ ROLL. 1 (1): 8. April 1985 – via Internet Archive. The Farm is this big barn like place with a stage at one end ad bleechers at the other.

We also worked with Jack Wickert – June 29, 1937 – January 1, 2018 : Community builder and musician, born in Wisconsin, raised in the Mission and Potrero Hill, friend to many, helper to all grassroots arts.

Graduated from Mission HS and SFSU, drove school bus and taxi. Played every kind of horn but called his trumpet his ego, till Vietnam War supporter smashed it into his lip as he marched with anti-war S.F. Mime Troupe band. Decked the fascist but soon lost front teeth. Switched to baritone.

In 1974, helped artist Bonnie Sherk plant cardboard cows in Cesar Chavez/101 maze, found second calling. Co-founded the Farm: community garden-gallery-school- theater-social hall in elbow of Potrero exit. Youth learned gardening, kids learned plants and animals, neighbors held weddings and funerals, performing artists rehearsed. Jack was manager, host, gardener, truck driver, janitor, plumber, cook, piano player, mentor to young staff and volunteers, till 10-year lease ran out just as rents rose. Farm fought to survive but lost, 1987.

After, led varied life. Travelled, mainly to Mexico with friends in his old school bus, lent hand at SOMARTS, Bayview Boat Club, Black Bear Ranch commune, marketed produce, taught music, played with Spitters brass band, held poker nights on his Mission Creek houseboat. In 2009, life of chainsmoking sent him to ICU with CPOD. After months of rehab went back to Camels, angering faithful visitors. Knew days were numbered. Died New Year’s morning.

On a Thursday in June 1970, a police officer in San Francisco was going nuts because motorists entering the busy Central Freeway near Market Street were jamming on their brakes, startled by an unusual sight. On what the day before had been a bare patch of ground, a young woman was sitting on a bale of hay, surrounded by potted palm trees and 4,000 square feet of green turf, patting a Guernsey calf that was tied to a railing.

“Keep those cars moving!” the anonymous officer shouted, according to an account in The Los Angeles Times.

“We could have a terrific pileup,” he added.

The woman on the hay bale was Bonnie Ora Sherk, and the temporary roadside attraction (created with the approval of highway officials) was the first in a series of conceptual art pieces she called “Portable Parks.”

“I like the element of surprise,” she told the newspaper, explaining that the idea was to reimagine empty spaces and inject a humanistic element into locations defined by anonymity and sterility.

“Freeways are beautiful, but they need to be softened,” she said. “Why use them just for cars?”

Ms. Sherk, an artist and landscape architect, went on to make a career out of unusual art projects that explored humanity’s relationship with nature. She died on Aug. 8 in hospice care in San Francisco, her sister Abby Kellner-Rode said. She was 76.

Ms. Kellner-Rode did not specify a cause. The death has not previously been widely reported.

Ms. Sherk, who lived in San Francisco, was among a group of artists in the late 1960s and early ’70s, many of them women, who sought to move the definition of art beyond painting and other traditional genres, creating momentary conceptual pieces that were site specific and performance based.

Bonnie Sherk talked me into opening a public office for community programs at THE FARM. She was a fire-storm of productivity and THE FARM was an incredible place:

Bonnie Ora Sherk (née Bonnie Ora Kellner; May 18, 1945 – August 8, 2021) was an American landscape-space artist, performance artist, landscape planner, and educator.[1] She was the founder of The Farm, and A Living Library. Sherk was a professional artist who exhibited her work in museums and galleries around the world. Her work has also been published in art books, journals, and magazines.[2] Her work is considered a pioneering contribution to Eco Art.[3]

Bonnie Ora Kellner was born on May 18, 1945, in New Bedford, Massachusetts. She grew up in Montclair, New Jersey. Her father Sydney Kellner was the area director of the American Jewish Committee and lecturer of art and architecture. Her mother was a first grade teacher.[1]

Sherk graduated Douglass College, Rutgers University in the 1960s.[4] She studied under Robert Watts at Rutgers, who taught her about the Fluxus movement.[1] She later enrolled in an MFA program at San Francisco State University.[4]

Sherk moved to San Francisco in the late 1960s[4] with her husband David Sherk.[1]

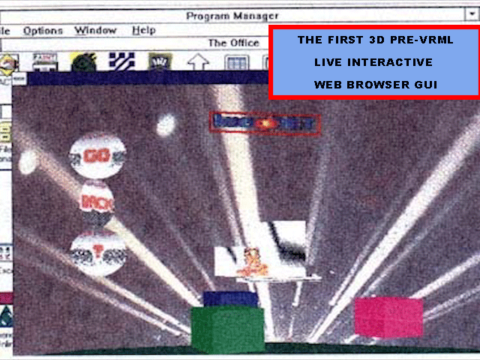

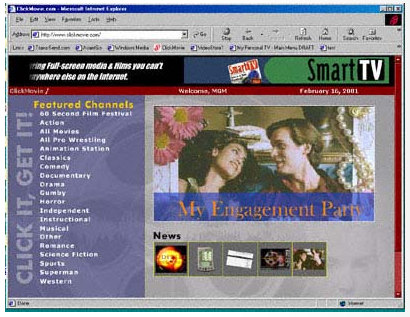

Sherk is a developer of a systemic, place-based approach to environmental transformation and education which links systems – biological, cultural, technological.[2] Integrated with such innovations, like Green-Powered Digital Gateways, Sherk’s approach incorporates interdisciplinary, standards-based, hands-on learning, community ecological planning and design, and state-of-the-art communications and technologies.[2] Sherk’s goal is to integrate local resources: human, ecological, economic, historic, technological, and aesthetic – seen through the lens of time – to make relevant ecological transformations, which are integrated with hands-on learning opportunities and community programs.[5]

In an interview with Peter Cavagnaro, Sherk shares her love and passion for the environment.[5] She believes that the environment is a “beautiful” and “diverse” place and that it is the most practical place for art and to create transformation, because it has the ability to reach communities near and far.[5]

- 2014, Vegetation As Political Agent, PAV, Parco Arte Vivente, Turin, Italy[6]

- 2017, Venice Biennale, Viva Arte Viva, May 13 – November 16, 2017.[7][8]

- 2019, Territorios que importan. Arte, Género, Ecologia, CDAN, Centro de Arte y Naturaleza, Huesca, Spain.[9]

Works

A Living Library (1980s–2021)

A Living Library[10] was Sherk’s ongoing work[11] she started in the 1980s, that consists of transforming environments -buried urban streams and asphalted public spaces, into thriving art gardens.[1] She has transformed these spaces in order to build education centers for children in communities in San Francisco and New York City.[12]

The Farm (1974–1980)

Created in 1974, and lasting through 1980, by Sherk, The Farm (also known as Crossroads Community) was a 7-acre eco garden and art space that spreads across traffic meridians and underused spaces under freeway overpasses. It even includes animals. This piece provided internships, educational activities for children, and acted as a public park throughout its duration.

Sherk felt that people lacked a “spiritual and ecological balance within ourselves and larger groups and nations,”[13] and felt that a space like the Farm could offer a solution to this issue through community connection, education, and creating a space within the urban landscape to uncover the natural environment that exists within the landscape and demonstrate our connection to life and the ecosystem.

Living In The Forest

Living In The Forest: Demonstrations of Atkin Logic, Balance, Compromise, Devotion, Etc. was an installation created in 1973 for De Saisset Museum in Santa Clara, conceived as a “a metaphor for life in all of its aspects, including birth, death, struggles for survival, compromise, living our daily lives, etc.”[4]

Public Lunch

Public Lunch[14][15] was one of Sherk’s most well-known performance pieces. The piece consisted of Bonnie eating lunch in cages with various animals, such as lions and tigers, at the San Francisco Zoo. She did this on a Saturday at 2pm in 1971, during normal feeding time and prime spectator watching.[5]

Sitting Still Series

In Bonnie Ora Sherk’s Sitting Still Series, 1970 (digital projection, photo documentation of performances) the artist sate for approximately one hour in various locations around San Francisco as a means to subtly change the environment simply by becoming an unexpected part of it. At the first performance, Sherk, dressed in a formal evening gown, sat in an unholstered armchair amidst garbage and creek runoff from the construction of the Army Street freeway interchange. Facing slow moving traffic, her audience was the people driving by. The following month Sherk sat silently in the midst of a flooded city dump at California and Montgomery Streets. Other locations in the series included the Financial District, the Golden Gate Bridge, and the Bank of America plaza. Sherk also continued her piece at the San Francisco Zoo in a number of indoor and outdoor animal cages. Sitting Still culminated in the performance Public Lunch, in which the artist ceremoniously ate an elaborately catered lunch in an empty cage located next to a cage of lions during public feeding time at the zoo. The project reinforced Sherk’s commitment to studying the interrelationship of plants, animals, and humans with the goal of creating sustainable systems for social transformation. The Sitting Still Series was exhibited in total as part of Public Works: Artists Interventions 1970s – Now, curated by Christian L. Frock and Tanya Zimbardo at Mills College Art Museum, September – December 2016; Sherk’s first image from the series graces the cover of the exhibition catalogue designed by John Borruso.[16]

In 1970, the first SECA Vernal Equinox Special Award, which recognizes conceptual and experimental projects, was presented to Sherk and Howard Levine by the SFMOMA.[17][18]

In 2001, Marion Rockefeller Weber‘s Arts and Healing Network awarded Sherk the 2001 AHN Award “for being an outstanding educator and for using her creativity to foster environmental healing.”[19]

Sherk was married to David Sherk. The couple later divorced.[1]

Sherk died on August 8, 2021, in San Francisco, California. She was buried on August 11 at the Mendocino Jewish Cemetery near the grave of her parents.[20]

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Genzlinger, Neil (November 19, 2021). “Bonnie Sherk, Landscape Artist Full of Surprises, Dies at 76”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Bonnie Ora Sherk, Author at Women Eco Artists Dialog”. Women Eco Artists Dialog. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ Weintraub, Linda (2012). To Life! Eco Art in Pursuit of a Sustainable Planet. University of California Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0520273627.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Galpin, Pierre-François (December 16, 2013). “Cultivating the Human & Ecological Garden: A Conversation with Bonnie Ora Sherk”. Independent Curatorial International. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Cavagnaro, Peter. “Q & A :: Bonnie Ora Sherk and the Performance of Being”. berkeley.edu. blook. Archived from the original on May 10, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ^ “Vegetation and politics”. www.domusweb.it. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ “Bonnie Ora Sherk and A Living Library Receive International Recognition at Venice Biennale 2017”. September 8, 2017.

- ^ “La Biennale di Venezia – Artists”. www.labiennale.org. Archived from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ^ “CDAN | TERRITORIOS QUE IMPORTAN” (in Spanish). Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ “A Living Library – Cultivating the Human and Ecological Garden | ROOSTERGNN”. ROOSTERGNN. September 9, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ^ “Focus Areas”. WCPUN. October 25, 2011. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ “Bonnie Ora Sherk”. greenmuseum.org. Green Museum. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ “A Living Library Crossroads Community (The farm): Early Life Frame Leads to Development of Potrero del Sol Park & A Living Library – A Living Library”. December 5, 2013.

- ^ “Writing”. Christian L. Frock. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ^ Frock, Zimbardo, Christian, Tanya (2015). Public Works Artists’ Interventions 1970s – Now. Mills College Art Museum. pp. 116, 117.

- ^ Frock, Christian; Zimbardo, Tanya; Hanor, Stephanie (2015). Public Works: Artists’ Interventions 1970s – Now. Oakland, California: Mills College Art Museum. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-9854600-2-0.

- ^ Desmarais, Charles (June 28, 2017). “SECA timeline”. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ “SECA Art Award History”. SFMOMA. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ “Bonnie Ora Sherk: 2001 AHN Awardee”. Art and Healing Network. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ Bonnie Ora Sherk (1945-2021) https://ecoartspace.org/Blog/10924774